Sikke and the War

Sikke during the Mobilization

This section contains the main points and key moments that appear in Sikke’s diary.

From Civilian to Soldier

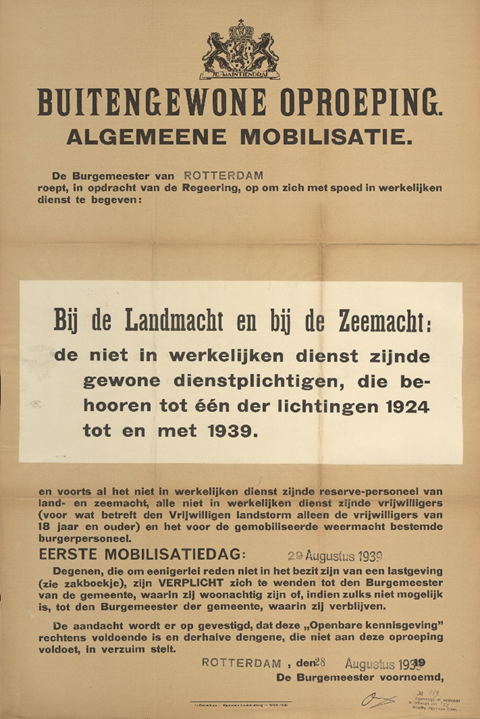

On August 24, 1939, the Dutch government decided to begin the preliminary mobilization of the Dutch army due to increasing international tensions. This early mobilization was intended to prepare for the full mobilization that would soon follow. Just a few days later, on August 28, 1939, the general mobilization of the Dutch army began. In total, approximately 280,000 Dutch men would be called to arms. Sikke was among them, as he was a conscripted soldier. He belonged to the 1925 batch, which fell within the mobilized batches (1924–1939/1940).[1] On August 28, 1939, Sikke decided to record his experiences in his war diary.

The poster (from Rotterdam), calling for the general mobilization.

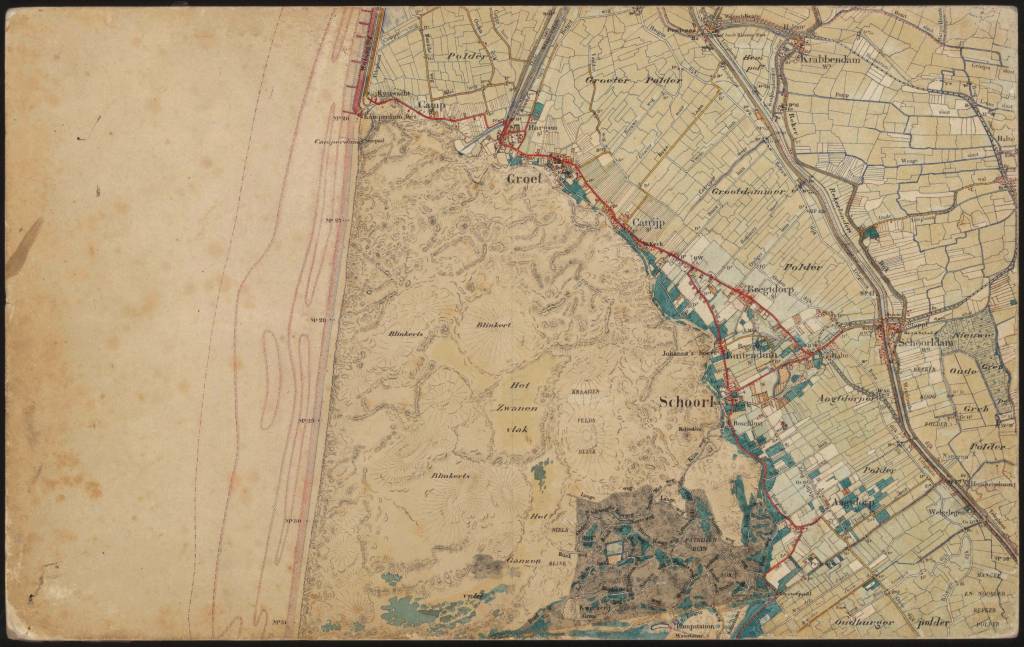

On August 29, he left his hometown, Hoorn, leaving behind his job and family in order to report to the depot battalion in Schoorl.[2] In Schoorl, he also reunited with some of his old comrades from his previous military service. Sikke was stationed at the Mennonite Brotherhood House (now known as Dopersduin) and assigned to the 3rd Company of the 9th Regiment Depot Battalion, III Depot Infantry.[3] Within this unit, he was part of the first section under the command of Lieutenant Hoogland.[4]

Schoorl was the first destination.

The Depot Battalion

The first Sunday of the mobilization was very busy in Schoorl, as many family members came to visit the soldiers. Sikke wrote the following about it in his diary:

“The first Sunday of the mobilization. In Schoorl, it is incredibly busy, with hundreds of cars from family members visiting the soldiers, causing traffic jams. Buses are coming from Frisia and Groningen, but I don’t have any visitors this Sunday. This Sunday goes by fast, and the summer weather is splendid. In the evening, everyone says goodbye to each other. The touching moments in a soldier’s life (I think of home).”

In Schoorl, Sikke received his equipment and weapon. He noted in his diary: “It is Saturday morning, and today the weather is getting warm again. To our regret, we receive a rifle and a few more pairs of socks.” It is likely that Sikke struggled with receiving a weapon, as he would have preferred not to use it against another person. He also received his military wage, 224 cents per week.[5] This was the amount he would receive during the mobilization. In addition, he was issued shoe polish for his boots, a straw sack to sleep on, a wartime pocketbook containing his military details, and an identification tag.

Sikke was not the only one in his family who had to serve in the military. His younger brother, Andries Hiemstra, was also called up. He was part of the Vrijwillige Landstorm, a militia organization of armed civilians that supported the regular army. Within this organization, he served in the Vrijwillige Landstormkorps Motordienst (Volunteer Motor Service Corps).

Eventually, Sikke’s younger brother Andries (nicknamed Manus) was also mobilized in 1939.

The Mannlicher M.95 was used by the Dutch Army during the Second World War. This rifle was also handed over to Sikke.

Military Duties and Training in Schoorl

Sikke carried out his first military duties in Schoorl. His very first assignment was digging trenches for the Air Protection Service. This was a group of volunteers who tried to protect the population from the consequences of air raids. One of the ways they did this was by constructing shelter trenches where civilians could hide during an air attack. In addition to digging trenches, Sikke also had to perform other military tasks, such as standing guard. On one occasion, he was on guard duty at Hotel De Roode Leeuw, and when he was relieved, he discovered that his new coat had been stolen. He reported this to the commander, but it is unknown whether Sikke ever got his coat back.

In the area around Schoorl, various military marches were held, in which Sikke had to participate as a soldier. He also underwent several types of training. He learned about rifles and the light machine gun, the Lewis M.20. Additionally, he took part in a gas drill in a gas chamber, as the army at the time was preparing for the possible use of chemical weapons in a future war. After all, these weapons had also been used during the First World War (1914–1918) and the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1937). There was also a blackout drill. In his diary, Sikke wrote the following about it:

“This evening, we are doing a blackout drill, all lights must be turned off. We are sitting with Jan Vries’ music, singing along with his harmonica (“We are not afraid”). Arnoldie reprimands us to be quiet: “It is duty,” he says.”

Sikke is in the middle of the group (wearing glasses and without a cap). The exact date and location of this photo are unknown, but it was likely taken near Schoorl.

Leisure Time and Prince Bernhard

Despite everything, Sikke naturally also had some leisure time. On Sundays, he often attended services at the Dutch Reformed Church in Schoorl (now known as the Dorpskerk Schoorl), or he would go for a walk in the surrounding area. There was also the construction of a canteen on the grounds of the Mennonite Brotherhood House. Once the canteen was built, it was used for film screenings and performances. Sikke had a great love for theater and cabaret, and he wrote extensively about the shows he saw during the mobilization. For instance, the famous cabaret performer Clinge Doorenbos gave a performance for the men in Sikke’s unit. In his diary, he wrote: “In the evening, Clinge Doorenbos performs for us. It is a wonderful evening, full of healthy humor. The song “There Comes a Time When We Will Go Back to Mother” is a big hit. Thank you, Captain Lopers.”

Sikke was also visited quite soon by his wife and children. On September 10, 1939, he wrote:

“At 1 o’clock, during lunch, I receive a visit from father, Ym, and the children. They have come by car from Hoorn. Little Siep is lying in a cradle in the car, and we take a trip to the sea, heading towards Camperduin. It is a beautiful day, and at 5 o’clock, they leave again for Hoorn.”

Finally, Sikke described a special moment he experienced in Schoorl. This event took place on September 29, 1939. He wrote the following:“t is a very important day because Prince Bernhard is visiting us. I had the great honor of speaking with him. He asked about home and a few other things. It is a moment I won’t soon forget.” It was not uncommon for members of the royal family, including Prince Bernhard, to visit conscripted soldiers during the mobilization period. This meeting left a deep impression on Sikke. After the war, he rarely spoke about his time during mobilization, except to mention that he had met Prince Bernhard.

Fort Uitermeer

Eventually, it was decided that Sikke’s battalion would be transferred to Weesp. On October 7, 1939, Sikke’s battalion was relocated to Fort Uitermeer, located in the municipality of Weesperkarspel (now Weesp). Fort Uitermeer was part of the New Dutch Water Line, a defense line designed to protect Amsterdam. Sikke was assigned to the 5th section, 2nd company, 1st battalion of the 31st Infantry Regiment.

However, upon arrival, it turned out that the barracks at the fort were not yet ready for occupancy. As a result, the soldiers were quartered at nearby farms. Sikke was quartered in the farm of farmer Galesloot. It was not until November 27, 1939 that the barracks were completed, meaning that during the first months of his transfer, Sikke stayed at the Galesloot farm.

This photo was taken at farmer Galesloot’s place. In the photo, Sikke (bottom left) can be seen together with his fellow servicemen.

This is Fort Uitermeer seen from the air. The famous fort where Sikke served and often spent his time as a soldier.

Military Duties and Training in Weesperkarspel

In the first week, Sikke and his fellow servicemen still felt homesick from Schoorl, as they had greatly enjoyed their time there. Nevertheless, they quickly began to feel at home at Fort Uitermeer. Just like in Schoorl, Sikke had to perform various military duties, such as preparing defensive positions, attending roll calls, transporting equipment, standing guard, carrying out outpost service, and maintaining his gear and weapons.[6] In addition, several marches were conducted to different locations, including Weesp, Hilversum, Hinderdam, Ankeveen, Nederhorst den Berg, Nigtevecht, Naarden, Bussum, and Bantam. In addition, the soldiers regularly went to the Sportfondsenbad in Amsterdam in order to swim.

Sikke also received a great deal of theoretical and practical training. He took theory classes on topics such as outpost service, the rifle, gas and gas masks, the machine gun, the pistol, military discipline, and general conduct. Various exercises were also carried out, including gymnastics, drills, battalion exercises, evening exercises, and shooting practice. On March 18, 1940, Sikke wrote about one of these shooting exercises: “We start the day with a roll call and then head to Weesp to shoot. It is very cold and freezing hard. In Weesp, I shoot very poorly the first time, scoring 31 out of 40, but the second time I score 37.”

Marching was an important part of military conscripts’ training. In this photo, you can see Sikke (the soldier with glasses) marching together with his fellow servicemen. The location and date of this photo are unknown.

Leisure Time, Military Meals, and Leave

Sikke regularly received military meals, such as brown beans or grey peas with bacon and buttermilk porridge, potatoes with beets and custard, or kale with sausage. As a result, Sikke was often responsible for peeling the potatoes.

Sikke also had free time, which he often spent with his fellow servicemen, such as A. Donker, W. Pelsma, J. Lanting, J. Tuininga, F. Groeneveld, Galema Veehouder, Klaas Cupido, and his best friend Jo van den Akker. Just like in Schoorl, he regularly attended the Dutch Reformed Church in Weesp on Sundays. He was also frequently found at the church’s military home. These homes were meant to offer soldiers a cozy environment outside the barracks where they could gather. At Fort Uitermeer, theater evenings, cabaret performances, parties, and film nights were also organized, often by O. en O. (Education and Recreation). These were committees that provided courses and activities for mobilized soldiers. Sikke was a big fan of such evenings. On December 12, 1939, he wrote:

“Tonight, I leave my post a bit earlier because there is an event at the fort. The Dutch Hague Cabaret is performing. A wonderful evening filled with singing, music, a ventriloquist, and a magician. A splendid evening of O. and O.”

Sikke also regularly listened to the radio for news or to hear performers, such as Wam Heskes with Miss De Bonk or Louis Noiret with Kobus Kuch.

Although Sikke tried to enjoy himself in Weesp, he longed deeply for home. He was a real family man and maintained strong ties with his father, brothers, sisters, wife, and children. When the mobilization began, he was 34 years old and had three children: Jan, Ank, and Siep. He regularly wrote letters to Hoorn (his place of residence) and Oudega (his birthplace), and tried to go on leave as often as possible to see his family again. On November 11, 1939, he wrote:

“Today is another day I get to go home on leave. This morning, I went to the fort twice, and after lunch, I freshened up a bit, shaved and so on. At 4 o’clock, I set off toward Weesp, and by half past 6, I’m in Hoorn. Everything is well at home. I brought back a little something from Weesp for the children, and everyone is content. The white bread from Ym tastes great, and I’m a civilian again for two days.”

This is Hoorn, the city where Sikke came from and where he lived together with Ym (his wife) and their children.

Espionage, Sabotage, and the Mobilization Winter

The mobilization of 1939–1940 brought several challenges, which also affected Sikke. The winter of 1939–1940 was exceptionally harsh, with temperatures dropping as low as minus 15 degrees Celsius. This winter, also referred to as the mobilization winter, disrupted military life. On January 29, 1940, Sikke wrote: “Upon waking, it is still winter, everything is an ice bank. Our barrack looks like an ice cave, with 1.5-meter-long icicles hanging from the roof. It is too cold for the march, so the day is spent indoors.” The mobilization winter would ultimately become the coldest since 1845 and the third coldest of the twentieth century, only the winters of 1947 and 1963 were colder.

During the mobilization period, espionage and sabotage also occurred, directly affecting Sikke’s leave. On November 9, 1939, the Venlo Incident took place, during which two British and one Dutch secret agent were abducted by the German Sicherheitsdienst. The abduction happened on Dutch soil, while the Netherlands was still neutral at the time. In the following days, reports appeared in newspapers, increasing the sense of approaching war. Therefore, Sikke’s leave was canceled.

Another incident that impacted military leaves was the Maasmechelen-Incident on January 10, 1940, near the Belgian town of Vucht. A German aircraft made an emergency landing there, carrying secret plans for the German invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (Fall Gelb). Belgian authorities passed this information on to the Netherlands. Initially, the Dutch were skeptical, but eventually decided to suspend all new leaves. Sikke’s leave was again canceled. He wrote:

“In the morning, Jo and I go to church as usual. After the service, we receive the news that leave has been canceled. We return downhearted to the barracks. […] Back in the barracks, there’s a discussion about the cancellation of leave. Belgium has also canceled its leaves.”

Despite this, Sikke would experience espionage and sabotage firsthand in February and March of 1940. On February 21, 1940, he spotted signal flares and wrote:

“After the afternoon roll call, I go on guard duty along the main road. From half past 11 to 12 o’clock, I observe signal flares in the direction of Hilversum. We stop and inspect all vehicles. We stand guard with loaded revolvers, and it is a busy night with a lot of variety. No further noteworthy news to report!”

To this day, the signal flares remain a mystery. In February and March, several newspapers reported sightings of flares in various parts of the Netherlands, often accompanied by unknown aircraft. These sightings were soon linked to espionage and sabotage. Even postwar historian Loe de Jong could not determine who was responsible for the flares. Sikke saw flares not only toward Hilversum, but also toward Nederhorst den Berg (February 25, 1940) and above Muiden (March 6, 1940). This flare affair caused unrest among both civilians and military personnel, as the party responsible remained unknown.

The Invasion of Denmark and Norway

In April 1940, tensions escalated when Nazi Germany decided to invade Denmark and Norway. The goal of this invasion was to secure the transportation of iron ore from Norway and Sweden, an essential raw material for German steel production. Nazi Germany wanted to prevent this resource from falling into British hands.

The invasion also affected Sikke’s battalion. It became possible that his battalion would be relocated, although it remained unclear in April where they might go. On April 20, the soldiers received word that they were to be transferred to Terneuzen. Sikke wrote:

“At half past 11 we receive our pay, and I am on guard duty until 2 o’clock. Our compy is ready to play a football match when the message comes to prepare everything for departure to Terneuzen. At 6 o’clock the entire battalion assembles, and at half past 6 we begin the march to Weesp, until a counter-order arrives: back to the barracks. There’s a great commotion in the barracks, and it is not until 1 o’clock in the night that things quiet down. The transfer appears to be postponed until further notice.”

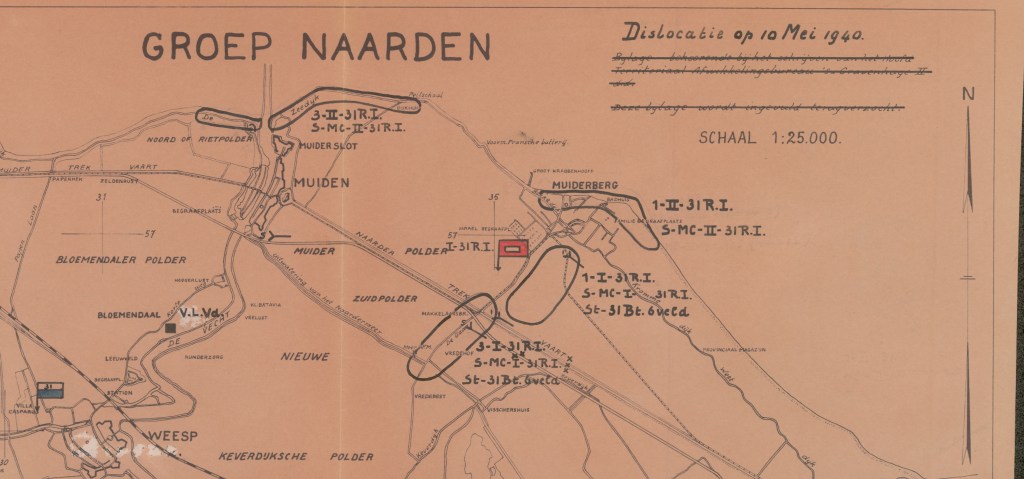

Ultimately, the transfer to Terneuzen did not go through. Instead, it was decided that the fifth section of the second company, to which Sikke belonged, would be reassigned to the first company. Therefore, Sikke was transferred to Muiderberg. There, he was placed in the first company, first battalion, of the 31st Infantry Regiment. He was stationed in a large warehouse named Coehoorn.

In Muiderberg, Sikke carried out military tasks similar to those in Weesp, such as standing guard and cleaning weapons. He also frequently attended church and took walks along the beach. Football matches were even held between the various companies on a nearby field. On April 30, 1940, Sikke noted: “Today, for the afternoon sport, we played football. The 1st compy against the 2nd compy (1–2), and the 3rd compy against the M. compy (1–7).”

This aerial photo of Muiderberg, taken in 1940, shows the location where Sikke was stationed as a soldier. Thus, Muiderberg became the third place where Sikke experienced mobilization.

Fort Coehoorn was a fort near Muiderberg that was originally intended to be part of the Defence Line of Amsterdam. Construction of the fort was halted after World War I. Nevertheless, prior to World War II, barracks and a warehouse were built on the fort grounds due to rising tensions. It is presumed that this warehouse is where Sikke spent the night. This photo shows the barracks after the war, when they were used to house Moluccan professional soldiers of the KNIL and their families.

May Days

On May 7, 1940, Sikke was scheduled to go home on leave, but all leave were canceled that day. This was related to the military attaché in Berlin, Bert Sas (1892–1948). Sas was in close contact with the German officer Hans Oster (1887–1945), who repeatedly warned him about a potential German invasion. Sas passed this information on to the Dutch authorities. On May 6, he reported that Germany would launch an attack on the Netherlands on May 8. In response, the Dutch government decided on May 7 to cancel all military leave. However, the anticipated attack on May 8 did not occur due to unfavorable weather conditions.

The actual invasion followed a few days later, on May 10, 1940. That morning, Sikke was awakened and prepared for the enemy’s arrival. He wrote the following about the event:

“At 5 o’clock in the morning, we are startled by the message from our C.C. that a German attack has been launched on our country. We immediately prepare ourselves and receive ammunition and hand grenades. We take up our positions behind Barrack Coehoorn. Strange aircraft fly over our country. One plane is fired upon by us and returns fire. The tension rises, although everyone remains calmly at their post, awaiting further orders.”

The German aircraft flying over Muiderberg were presumably targeting Schiphol. Schiphol, from a military standpoint, held a strategic position and was therefore bombed on May 10. However, it’s also possible that some strategic positions in Muiderberg itself were attacked, as the village was filled with bunkers that were part of the New Dutch Waterline.

This is a military map of the situation on May 10, 1940, in the area around Muiderberg. The map also shows the positions held by Sikke’s company (1-I-31 R.I.).

On May 11, Sikke’s company was transferred to Amsterdam, where he remained during the German invasion. The unit was tasked with engaging German paratroopers and apprehending suspicious individuals. The situation in the capital was chaotic. The city was gripped by the “paratrooper fever,” during which many Amsterdam residents thought they had seen German paratroopers, though none were actually present. People were also afraid of the “fifth column,” a group consisting of members of the NSB, Nazi sympathizers, and Germans living in the Netherlands. There were fears that the fifth column would carry out acts of sabotage that would support the German advance. A rumor even circulated that the fifth column was distributing poisoned chocolates.

The Dutch army, police, Air Protection Service, and Volunteer Civil Guard all conducted checks on the citizens and each other, sometimes leading to dangerous situations. During the May Days, there were also suicide attempts, many of them in Amsterdam. A significant number of these were carried out by Jews who feared living under a Nazi regime. In Amsterdam, approximately 400 people are believed to have taken their own lives during the German invasion.

The situation in Amsterdam made a deep impression on Sikke. In his diary, he wrote:

“Just like other mornings, there are once again airplanes coming under fire from anti-aircraft guns. Bombardments only took place in the Heerengracht on Saturday, May 11, during which 40 people lost their lives. Tension hangs over the city. The police and military are working hard, arresting many individuals who appear suspicious. More than I can write, we are living through this day. We are very tired, but we do our duty. Hundreds are being detained by us.”

On May 11, 1940, a bombing took place in Amsterdam near the Blauwburgwal and the corner of the Herengracht. The attack resulted in 44 deaths and 79 injuries. Additionally, 14 buildings were destroyed. There are two explanations for this bombing. According to the first, a German bomber was targeting Schiphol. However, the aircraft was hit by Dutch anti-aircraft fire, causing the bombs to be dropped over Amsterdam to lighten the load. Another explanation is that the old post office behind the Royal Palace on Dam Square was the actual target, as it housed the communication center of the Dutch army.

On May 14, Sikke was transferred to Amsterdam-Noord. The reason was that unverifiable messages had suggested the Afsluitdijk had been breached and that German troops might reach North Holland by crossing the Zuiderzee (now the IJsselmeer) with small boats. In his diary, he wrote:

“At 4 o’clock we are startled by the sound of the immediate alert alarm. We are ready at once and transferred to the opposite side of the IJ in connection with preparing positions to repel the enemy.”

All in all, the May Days in Amsterdam were extremely chaotic, and the German invasion likely left a deep impression on Sikke.

Prisoner of War and Demobilization

On May 15, 1940, after five days of fighting, the Netherlands surrendered. This capitulation marked the beginning of the demobilization of the Dutch army. After the surrender, Dutch soldiers gradually returned to civilian life. The full demobilization process lasted until July 1940. Sikke’s company was taken as prisoners of war. In his diary, he wrote:

“Yesterday afternoon, the news arrived that the Netherlands had surrendered. We are transferred to the Beatrixschool, where we spend the night and hand in our weapons. At 2 o’clock, we have to go to the stadium, from where we are moved to the school at Frans Halsstraat 16. There, we are considered prisoners of war. The tension has eased slightly, but there is still mourning due to the losses in our army. At 8 o’clock, we go to bed without our uniforms for the first time again. We are exhausted.”

In Amsterdam, Sikke’s company was first stationed at the Beatrix School and later at the Frans Hals School. He remained at the latter during his captivity.

Sikke was soon visited by his wife, who had searched for him for two days. He was also allowed relatively free movement within Amsterdam. On the first Sunday after the capitulation, he visited the Oude Kerk and the Muiderkerk. Sikke’s company was also allowed to bathe at the Sportfondsenbad or visit Amsterdam’s zoo, Artis. Nevertheless, they still had to carry out military duties. Exercises continued at the sports field near the Museumplein, and Sikke was assigned to guard powder ships or stand watch at the Hembrug.

On May 27, 1940, soldiers from Sikke’s company were granted extended leave to return home. Sikke himself received permission to go on extended leave on May 30, 1940. He wrote his final diary entry on May 31, 1940:

“Today I met acquaintances and family, and spoke with many of them. Tomorrow I will return to work at the PWN.[7] I have experienced a great deal during the time in which this book was written. I sincerely hope that war will never again come upon us. Thank God that all those dear to me have been spared. On this day, Friday, May 31st at 8:30 in the evening, I close my diary, and may I remember this longing with gratitude for a long time to come.”

This is a photo from after the war. On the left, the gate of the Frans Hals School can be seen. This was the place where Sikke stayed as a prisoner of war.

[1] Batches are groups of soldiers that are called up together for military service.

[2] The depot battalion served as a training center for incoming draftees.

[3] In 1939, a company consisted of about 160 men, a regiment of about 2,500 men, and a battalion of about 750 men.

[4] In 1939, a section was composed of 30-34 men (approximately).

[5] This amounts to approximately €59.13 per week (without taking the exchange rate into account) and €26.83 per week if you do take the exchange rate into account.

[6] The outpost service is a security service for resting troops. Soldiers on outpost duty warn resting troops of a potential attack and can temporarily hold back the enemy if necessary.

[7] PWN stands for Provincial Water Supply Company North Holland. This is a drinking water company based in North Holland, where Sikke worked.

Sikke’s family during the Second World War

Sikke was a family man and had a strong bond with his father, brothers, sisters, wife, and children. After all, the Hiemstra family was a very close family. Therefore, this section will also focus on his family and what they experienced during the war. The information in this section is based on conversations with family members, books, and archival material.

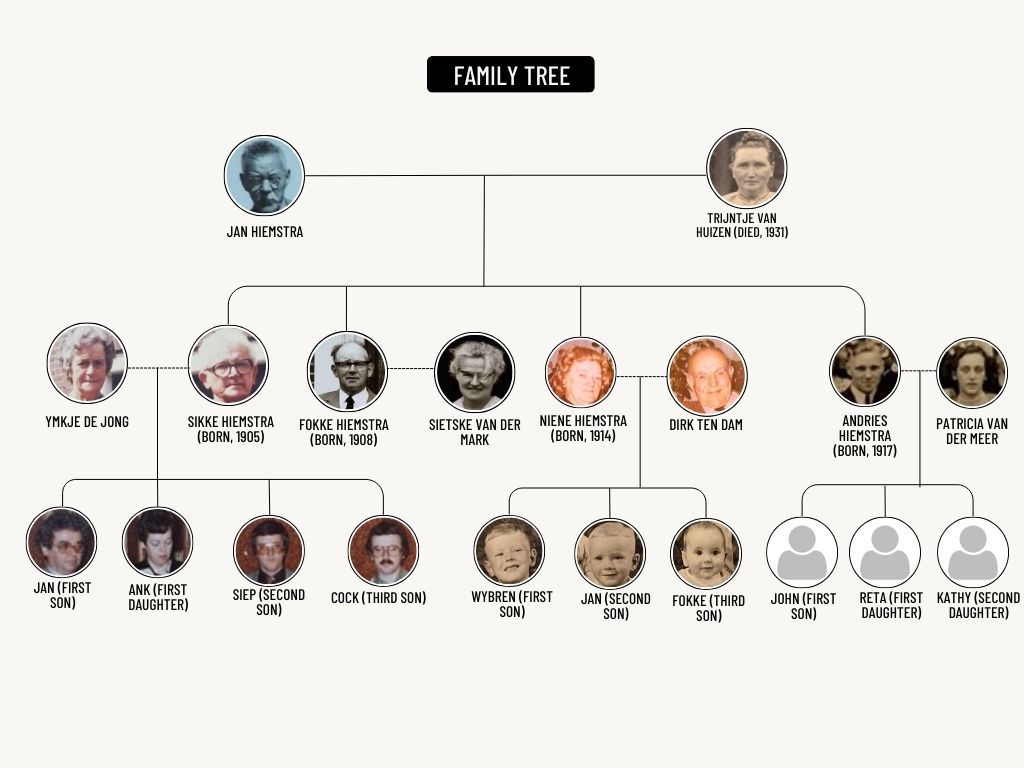

This is a family tree of the Hiemstra family during World War II (1940-1945).

Jan Hiemstra (father of Sikke)

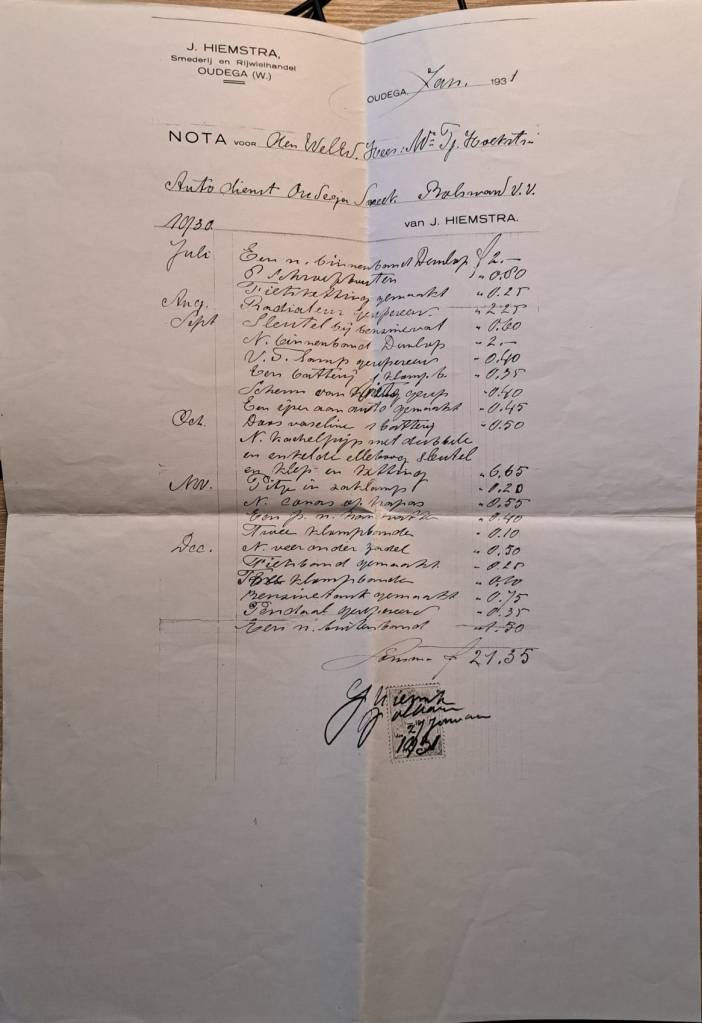

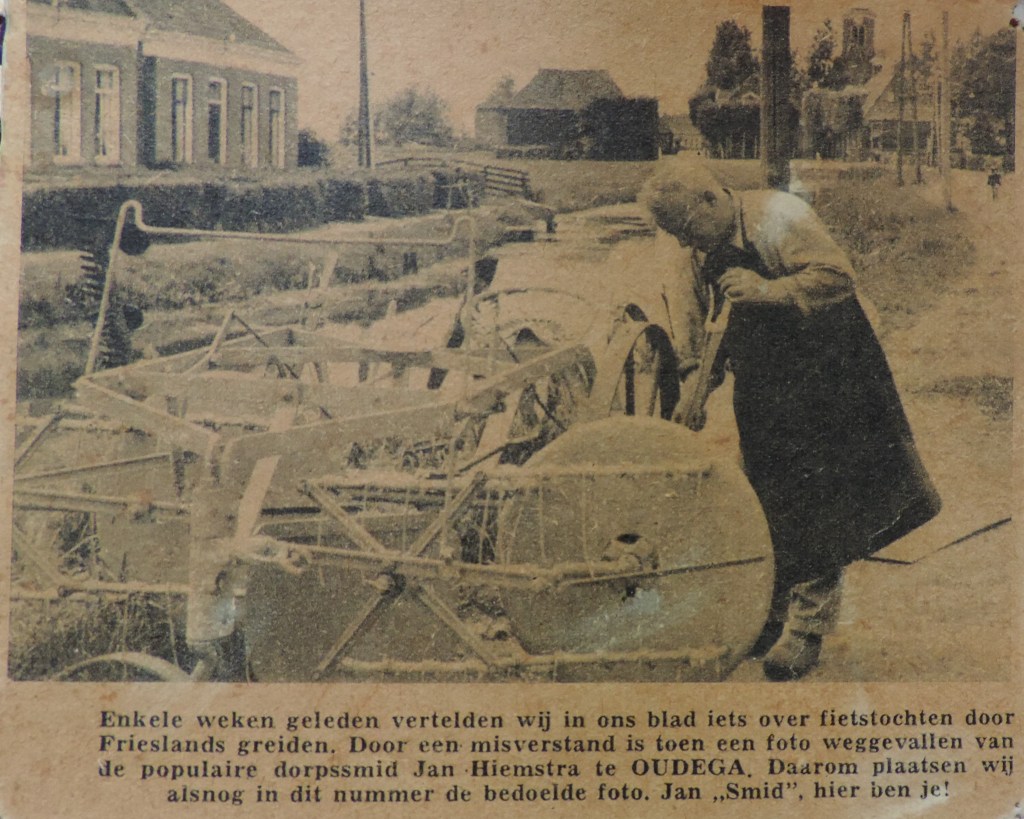

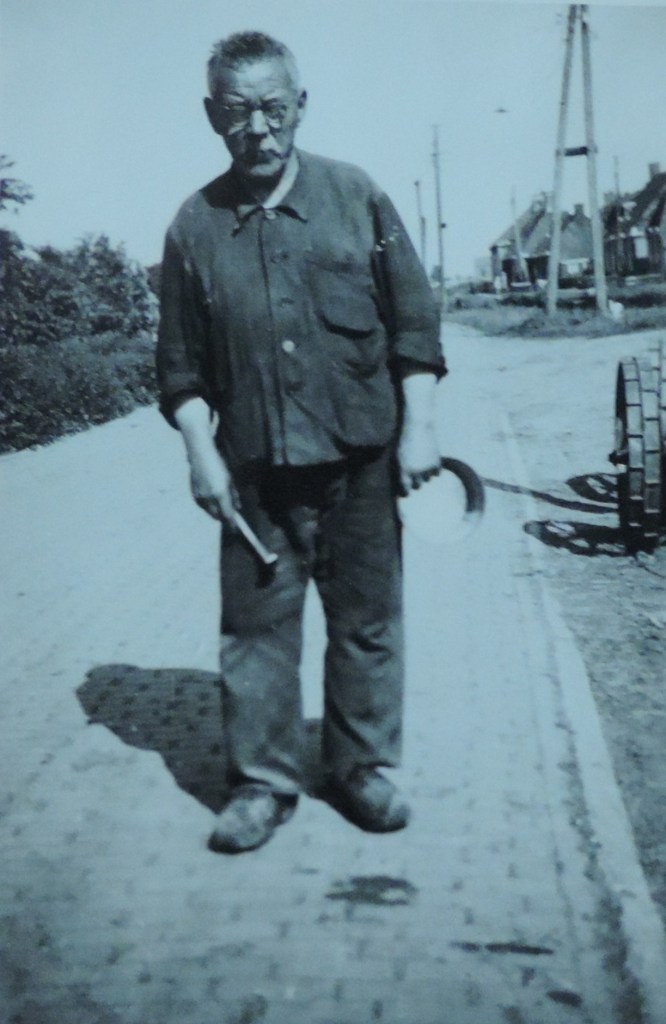

Sikke’s father, Jan Hiemstra (1876–1951), lived in Oudega (W.) and worked there as a blacksmith and bicycle dealer. In the village, he was therefore known as Jan Smith. He collected payments only once a year. If people did not have enough money to pay him, he would let them off the hook entirely. This naturally made him a beloved figure in the village. His word carried weight, even though he himself did not wish to hold any position of authority.

Fokke and Jan Hiemstra in front of the blacksmith.

A photo of the blacksmith’s bill. This bill dates back to 1931.

When the Second World War broke out, it also had consequences for Jan. Two of his sons, Sikke and Andries, were mobilized for the Dutch army in 1939–1940. Shortly afterward, Nazi Germany occupied the Netherlands. Therefore, Jan developed a hatred for the Germans. Little is known about his life during the early years of the war, but he presumably continued working in his blacksmith.

However, Jan increasingly became involved with the resistance. He was responsible for making light boxes used to mark the drop zones for weapons. This did not mean that Jan was an active member of the resistance himself, but he did carry out tasks for them. In addition, Jan secretly owned a radio, something that was strictly forbidden by the German occupiers. Nevertheless, the entire village would come to his house on the Lyspôlle to listen to broadcasts from Vrij Nederland or Radio Oranje. The resistance warned him that he could be betrayed, but Jan did not believe it. However, things went wrong in October 1943.

On a Saturday evening, Jan was listening to Radio Oranje together with a few fellow villagers. That same evening, German soldiers entered Oudega and raided Jan’s house. In a panic, people tried to escape through the windows. The Germans immediately opened fire, wounding two people: Ids Verbeek and Sjouke Abma. The other ten present were arrested, although one of them managed to escape. It was never discovered who betrayed Jan Hiemstra.

This cabinet stood in Jan Hiemstra’s room when he was betrayed. He lived in a small house, which meant people were closely packed together when listening to the radio. The dark patches on the cabinet show where people stood with their wet coats pressed against it.

According to family stories, Jan had to walk to Sneek in his socks. From there, he was taken to Assen. He eventually ended up in the penal camp Port Natal. There, he was put to work on the construction of a defensive line. Although the supervision was relatively lax, Port Natal was known as a notorious penal camp. It was also referred to as “Port Satan.” Prisoners were abused, and corporal punishment was common. Jan was not only imprisoned with his fellow villagers, but also with forced laborers from Texel and even Russian prisoners of war. It is believed that Jan managed to escape around November or December 1944 and returned to Oudega. The resistance in Oudega most likely provided him with false papers upon his return.

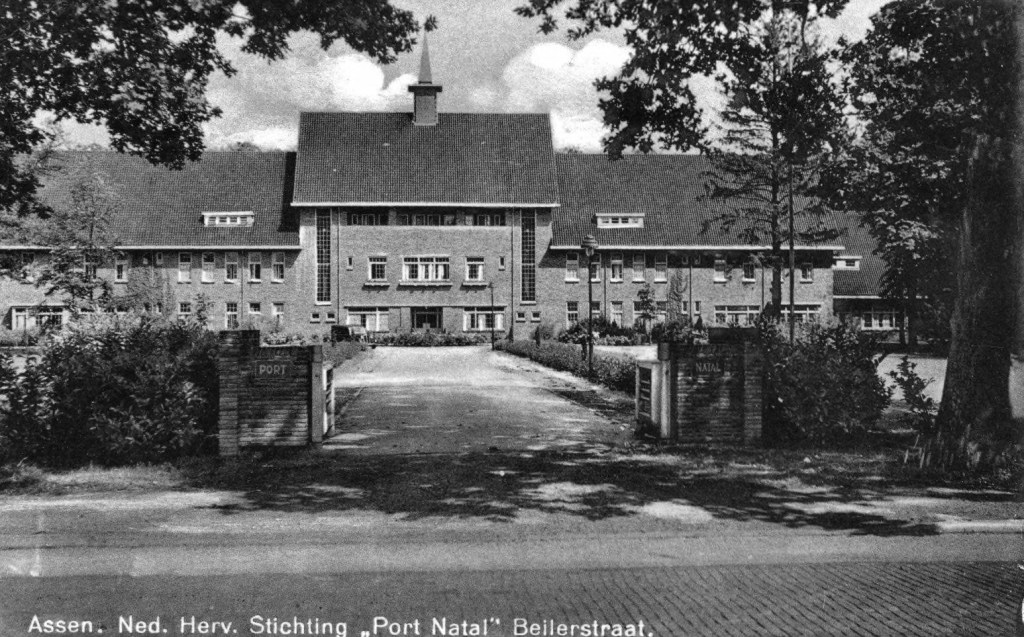

A photo of Port Natal, former sanatorium, from the period 1937–1940.

A drawing by Sjoerd Hannema depicting prisoners from Port Natal forced to work on a trench.

It is quite possible that Jan met the politician Willem Aantjes (1923–2015) in Port Natal. In 1944, Aantjes joined the Germanic SS in order to avoid compulsory labor. However, this required him to swear allegiance to Adolf Hitler. According to Aantjes himself, he refused to do so and was imprisoned in Port Natal, where he was initially forced to dig trenches. Later, he became an assistant to the camp administrator. In the 1970s, he became the parliamentary leader of the ARP and later of the CDA, but had to resign due to his wartime past. Sikke and his wife, Ymkje, strongly disliked Aantjes, which likely kept them from ever voting for the ARP or the CDA. This makes a meeting between Jan and Aantjes in Port Natal plausible. Jan eventually witnessed the liberation of Friesland in April 1945.

A photo of parliamentary group leader Willem Aantjes during a press conference about his wartime past and departure from politics.

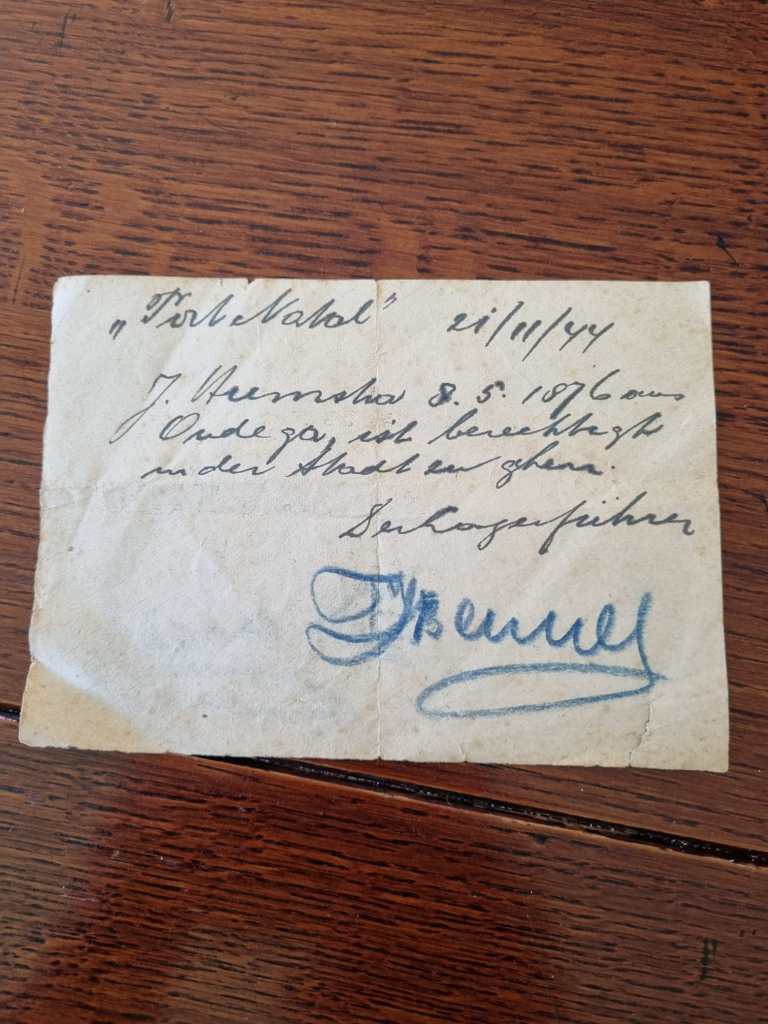

A (leave) note signed by the Lagerführer (camp leader). The note states (in German): J. Hiemstra, May 8, 1876, from Oudega, has the right to enter the city. He likely used this note to escape.

Sikke Hiemstra & Ymkje de Jong

Sikke was the first in his family to experience World War II up close. As a soldier, he witnessed the German invasion and shortly thereafter spent time as a prisoner of war. On May 30, 1940, he was allowed to return home and resumed civilian life after having served nine months in the Dutch army. Sikke went back to work at PWN and was responsible for the construction of water pipelines in North Holland.[1]

Sikke (left) and Jan (right) together in a photo.

Although Sikke and Ymkje were not actively involved in the resistance, they did take part in passive resistance. This often consisted of small actions. For example, orange marigolds were planted in Pieter Florisstraat to show support for the Dutch royal family, something that Sikke and Ymkje also participated in. Furthermore, Sikke occasionally siphoned gasoline from German vehicles as a form of passive resistance.

Planting orange marigolds was a well-known form of silent resistance among the Dutch.

Sikke was also exempt from being sent to Germany as a forced laborer because he worked for the PWN. He had a crucial job, as he was responsible for installing water pipelines and measuring the water levels. Nevertheless, the war came close to him as well. In 1944, two Allied planes collided above Hoorn and crashed. Sikke was cycling from his job when he saw the aftermath of the crash. He saw debris and the bodies of fallen Allied soldiers. Eventually, he was sent away by German soldiers.

The war would affect Sikke’s family in another way as well. In September 1944, the southern part of the Netherlands was liberated by the Allies. The Dutch government in London called for a railway strike in the south, which brought coal transportation from South Limburg to a halt. As a punishment, the Germans decided to block food shipments. The winter of 1944-1945 was severe, and there was a serious food shortage. This led to famine, especially in the large cities in the western cities of the Netherlands. Ultimately, about 20,000 people died during the hunger winter of 1944-1945.

Sikke’s family was also affected by the Hunger Winter. In order to survive, they ate, among other things, a swan from the city pond and tulip bulbs. Ymkje regularly visited farmers in the area around Hoorn. She had once run a cheese shop, so it’s quite possible that she knew some of these farmers. Unfortunately, some farmers took advantage of her situation, something that Ymkje remained bitter about later in her life. In addition, Ymkje often undertook hunger journeys to Friesland in order to collect milk and eggs from farmers there. Friesland was more agricultural and suffered less from food shortages. Their eldest son, Jan Hiemstra, was sent to live with relatives in Friesland, so there would be one less mouth to feed at home during this difficult time. Sikke also tried to obtain food. He frequently had to measure water levels in places where German soldiers were stationed. Therefore, he managed to get kuch, ammunition bread, from the Germans.

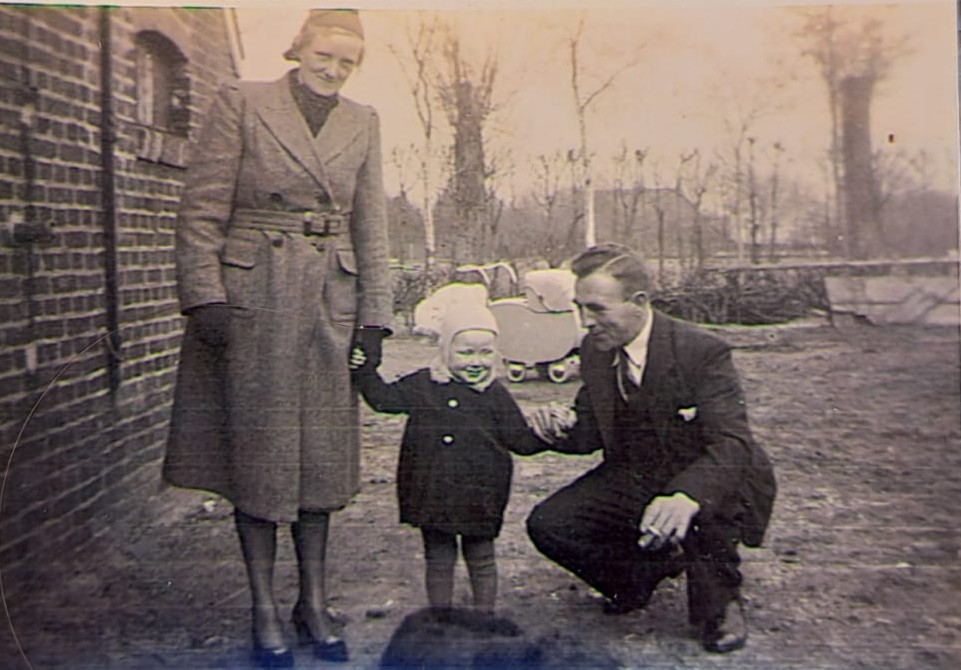

A pre-war photo of Sikke, Ymkje, and their eldest son Jan.

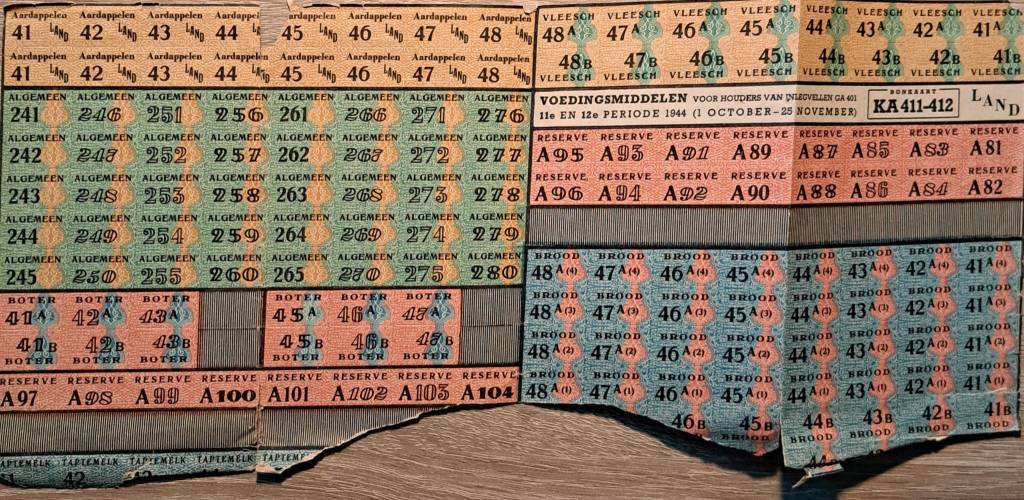

These were food coupons from Sikke Hiemstra and Ymkje de Jong during the period October-November 1944.

This period must have been especially difficult for the family. After the war, Ymkje harbored a deep hatred towards the Germans, likely as a result of the occupation and the Hunger Winter. Eventually, Hoorn, the city where Sikke and Ymkje lived, was liberated in May 1945.

Tiete Hiemstra (sister of Sikke) & Jeen Hornstra

Tiete Hiemstra (1908–1940) was the younger sister of Sikke. In 1937, she married Jeen Hornstra (1900–1945). On July 2, 1940, they had a son together, Fekke Hornstra (1940–2015). Shortly thereafter, Tiete passed away on October 19, 1940, due to complications from the pregnancy. This was, of course, a difficult time for the Hiemstra family, including Sikke. The family lost a mother, wife, daughter, and sister in the early years of the war.

This is Tiete with her husband Jeen. This photo was likely taken during their wedding.

A photo with Fekke Hornstra, son of Tiete Hiemstra and Jeen Hornstra, together with Jan Hiemstra (father of Tiete Hiemstra). This photo was taken around 1940.

Despite this, Jeen Hornstra maintained contact with the Hiemstra family after the death of his wife. In 1943, he married Baukje van Dijk (1906–1996). Toward the end of the war, Jan Hiemstra, the eldest son of Sikke Hiemstra and Ymkje de Jong, temporarily stayed at Jeen’s farm in Wyckel due to the Hungerwinter in Hoorn. In Friesland, tensions and resistance activities increased during this period. Jeen Hornstra also became involved in this. Resistance members tried to obtain weapons through supply drops in the area. One day, something was about to go wrong with the transport of these weapons, and a cousin (member of the resistance) of Jeen asked if the weapons could be stored overnight in his barn. Jeen agreed, as it would help his cousin. The next day, the weapons were transported further.

This was the farm of Jeen Hornstra in Wyckel.

Jeen Hornstra together with his newborn son, Fekke Hornstra.

This act ultimately proved fatal for him. On February 19, 1945, German soldiers surrounded Jeen’s farm in search of weapons. Jan, Sikke’s and Ymkje’s son, was also witnessed the German raid on the farm and was held at gunpoint by the German soldiers during the raid. Although no weapons were found, the soldiers still took Jeen with them. On April 7, 1945, just a week before the liberation of Friesland, he was executed by the Germans as a reprisal measure.

Until that moment, Jeen had not been involved in any resistance activities. His decision to help his cousin cost him his life. Jeen left behind a son, Fekke Hornstra, who later in life struggled greatly with the loss of his parents. After the war, Jeen was honored with a memorial torch at his grave in Wyckel. Jan Hiemstra (father of Sikke and Tiete) accepted this torch on behalf of the family. To this day, commemorations are still held at his grave on May 4. His name was also added to the war memorial in Balk, and a street in Wyckel was named after him.

On the left is the grave of Jeen Hornstra with the memorial torch. On the memorial torch is written in Frisian:

“Fell in the fight against injustice and slavery, so that we may wake up in peace for justice and freedom.”

On his grave is written: “Here rests until the day of resurrection our dear husband and father Jeen Hornstra, born in Koudum May 22,1900, died in Doniaga March 17, 1945 Hymn 260 verse 2 Boukje Hornstra van Dijk Fekke.” On the right is the grave of Tiete Hiemstra and Fekke Hornstra.

The monument in Balk. In Frisian it says, ‘Fallen in the fight against injustice and slavery, so that we may wake up in peace for justice and freedom.’ On the monument are five names of people who died during World War II.

Fokke Hiemstra (brother of Sikke)

Sikke’s younger brother, Fokke Hiemstra (1912–1989), lived in Oudega (W.) like their father, Jan Hiemstra, and worked as a postman. His nickname was also Fokke Post since he was a postman. He was a modest and reserved man, and one of the few in the family who could drive a car. However, it is unknown whether Fokke, like his brothers Sikke and Andries, was required to serve in the military. What is clear, though, is that he too experienced the consequences of the war.

Fokke ‘Post’ poses (on the left) together with a colleague in a photo.

Fokke Hiemstra with Jan Hiemstra (son of Sikke) and Fekke Hornstra (son of Tiete).

During World War II, many Dutch citizens were forced to work in Nazi Germany to support the German war economy. Hundreds of thousands of young men were required to report or were arrested to be used as forced laborers. Many went into hiding to escape this fate.

Fokke was no exception. It is unknown whether he was arrested or voluntarily reported himself to the authorities, but archival material shows that he was eventually forced to work in Nazi Germany. In 1944, he worked for the Deutsche Reichspost (German Reich postal service), presumably due to his background as a postman. At that time, he was living in Herford. He later worked at the Telegrafenbauamt (telegraph construction office) in Herford and stayed in Eickum (a small town near Herford). In Nazi Germany, Fokke was mainly employed by public institutions or companies involved in social security. The situation could have been worse for Fokke, because he was not assigned to work in the war industry. In fact, he worked for Germans who were opposed to Hitler and had a good relationship with them. Fokke likely remained in Germany as a forced laborer until the end of the war.

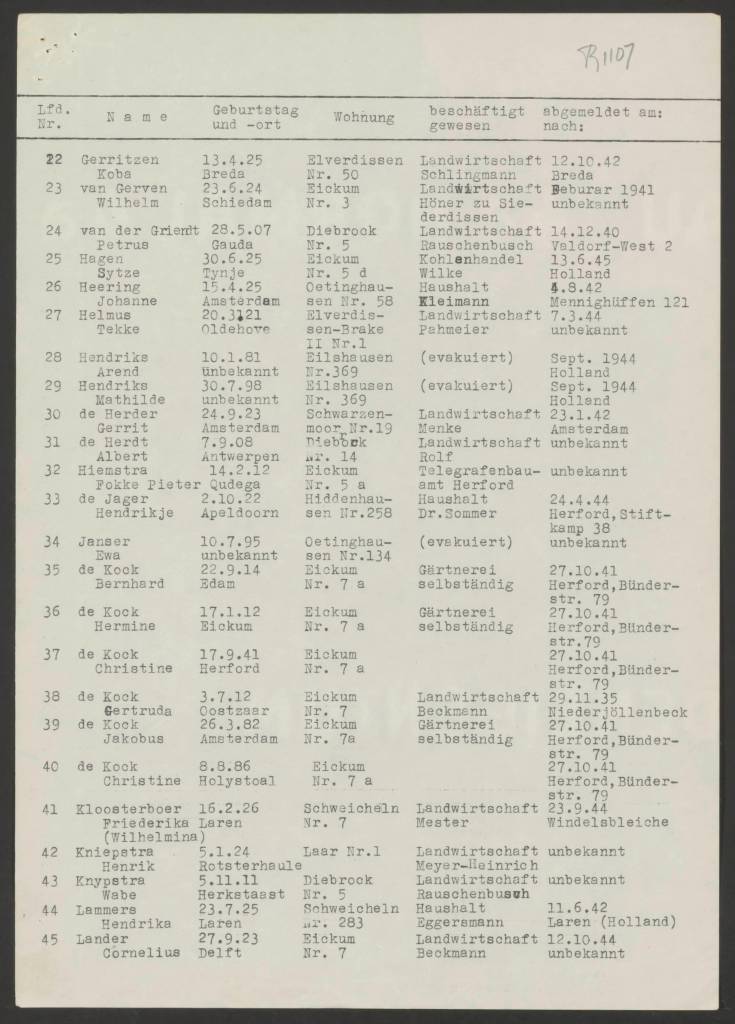

This is a list from the Dutch Red Cross of Dutch citizens who worked as forced laborers in Germany. At number 32 is the name of Fokke. It also states that he lived in Eickum and worked for the Telegrafenbauamt (Telegraph Construction Office) in Herford.

Niene Hiemstra (Sister of Sikke) & Dirk ten Dam

Sikke’s youngest sister, Niene Hiemstra (1914–1990), stayed in Oudega during the war, just like Fokke. She was a cheerful, hospitable, and kind woman. Niene worked hard and enjoyed chatting with others. She primarily spoke Frisian (minority language) because she did not have a good command of Dutch. Nevertheless, she could speak Dutch, although she preferred Frisian. The death of her sister Tiete in 1940 likely had a profound impact on her. It left her as the only sister remaining in the family.

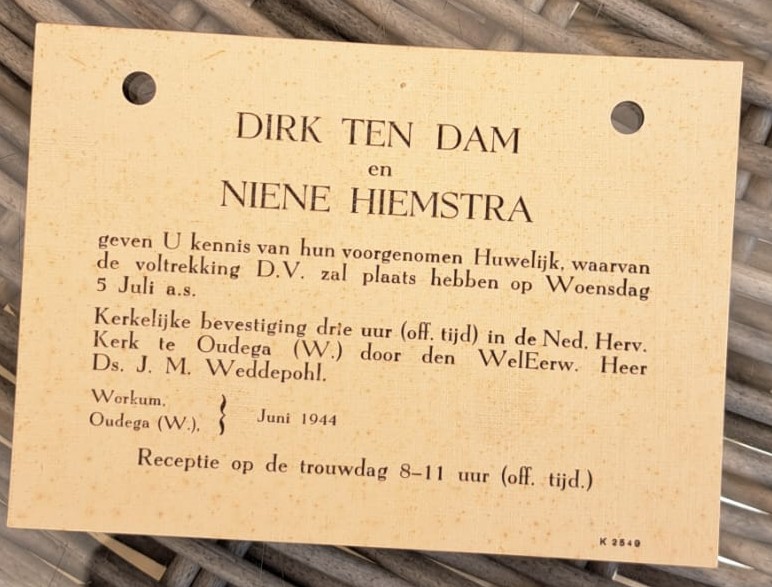

Niene also married her husband, Dirk ten Dam, on July 5, 1944. Unfortunately, her father, Jan Hiemstra, and her brother, Fokke Hiemstra, could not attend the wedding. Her father had been imprisoned in Port Natal since October 1943, and her brother was forced to work in Nazi Germany. It is very likely that this was difficult for her, as the Hiemstra family was a close family. After the wedding, Niene and Dirk moved to Easterein. This was not easy for Niene, as she felt deeply connected to her birthplace, Oudega (W.). During the war, Dirk ran a butcher shop, where Niene often helped him.

Niene (left), Fekke (center, son of Tiete and Jeen), and Dirk (right) together in a family photo.

Invitation to the wedding of Dirk ten Dam and Niene Hiemstra.

Not much else is known about how Niene and Dirk experienced the rest of the war. However, it is known that Niene witnessed a bombing up close during the war. Her younger brother, Andries Hiemstra, wrote the following in a letter to Jan Hiemstra:

“Nine is doing well, but this incident [Jan Hiemstra’s arrest] did not help. On Sunday, the station was also bombed, she had even gotten out of bed, but everything turned out all right.”

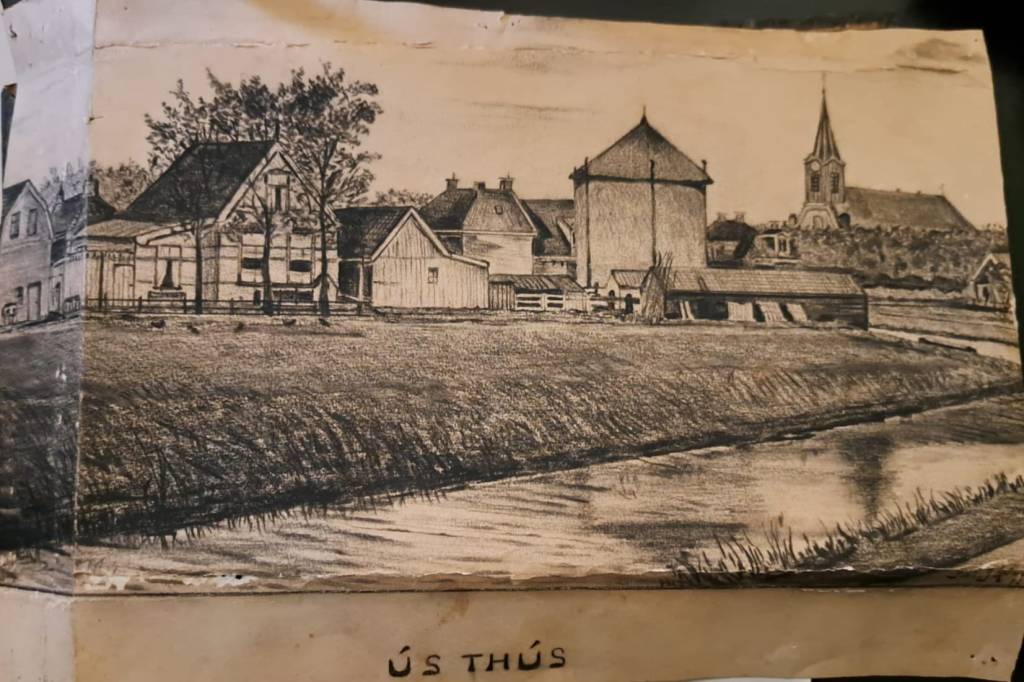

This is a drawing made by Sikke in the 1930s. The drawing shows the Lyspôlle in Oudega (W), with the church in the background. At the bottom of the drawing, it says in Frisian ‘Our home’. This was the village Niene longed for after she left it in 1944.

Andries Hiemstra (brother of Sikke)[2]

Like Sikke, Andries Hiemstra (1917–2013) returned unscathed from military service. Andries had a flamboyant personality and was a true adventurer. He was also known within the family as Manus, because of his large hands. Like Fokke, Niene, and his father, he lived in Oudega (W.) and worked as an apprentice blacksmith in his father’s forge. Around 1942, Andries decided to join the resistance. According to him, he helped Jewish people go into hiding, sabotaged railway lines, collected weapons that were dropped by aircraft, and cut down trees to hinder German traffic.

When his father, Jan Hiemstra, was arrested by the Germans in October 1943, Andries was not at home. He decided to write a letter to his father. From that letter, it is clear that Andries struggled greatly with his father’s arrest. He also sent letters to Sikke, Fokke, and Niene to inform them about the situation. Andries then went into hiding and obtained a false identity card under the name Dirk de Vries. He stayed on a farm outside Gaastmeer, where he helped burn peat.

Andries remained active in the underground resistance, helping people in hiding, including Jews, and facilitating weapons deliveries. He also worked as a bicycle courier. According to him, he was shot at and pursued by Germans during one of his deliveries. He had to hide in a ditch to avoid arrest. He frequently had to go into hiding from the German occupiers, which likely led to lasting health issues.

A group photo featuring six members of the Dutch Internal Armed Forces (NBS), taken after April 15, 1945, near Obbema. From left to right: Andries Hiemstra from Oudega (W), Gatse de Groot from Oudega (W), Rients Oppewal from Oudega (W), Dr. Jan Bonga from Woudsend, Ekke Atsma from Leiderdorp, and Jan Tjittes Piebenga from Oudega (W).

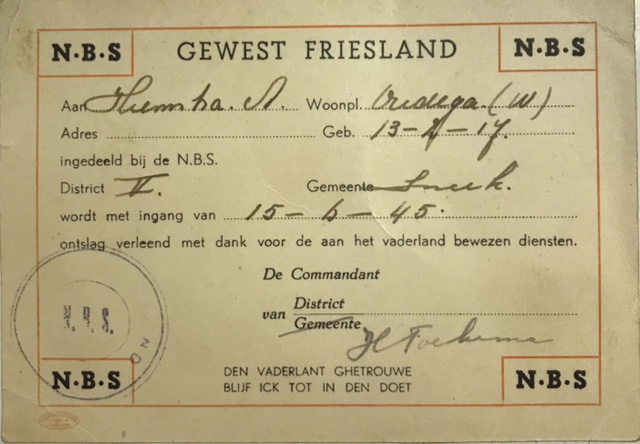

Toward the end of the war, the Dutch Internal Armed Forces (NBS) were established by royal decree, under the leadership of Prince Bernhard (1911–2004). The purpose of this organization was to unite resistance groups in order to jointly fight the Nazi regime. Andries also joined the NBS. According to Andries, he helped with the derailment of a munitions train. On April 12, 1945, just before the liberation of Friesland, the German army sent a munitions train from Leeuwarden to Stavoren. The NBS managed to derail the munitions train before it could reach its destination. After the war, Andries helped with the capture of German soldiers. Eventually, Andries was honorably discharged by the NBS on June 15, 1945.

An NBS card, in which Andries is honorably discharged effective June 15, 1945.

Andries received a bronze commemorative badge for his service within the Dutch Internal Armed Forces.

[1] PWN stands for Provincial Water Supply Company of North Holland. It is a drinking water company based in North Holland, where Sikke worked.

[2] After the war, Andries attempted to apply for a resistance pension, as he had sustained permanent injuries during his resistance activities. His application was processed, and he had to undergo several interviews. Unfortunately, his application was rejected because no one could verify his claims. Many of the people involved had already passed away, as he only submitted the application sometime between the 1990s or 2000s. The information for this part was obtained through interviews with the son of Andries Hiemstra and by requesting the interview transcript of Andries Hiemstra from the Social Insurance Bank.

Sikke’s family after the Second World War

Sikke was a family man and had a close relationship with his father, brothers, sisters, wife, and children. After all, the Hiemstra family was a very close family. Therefore, this section will also focus on his family and what they experienced after the war. The information in this section has been compiled based on conversations with family members, books, and archival materials.

This is a family tree of the Hiemstra family after World War II.

Jan Hiemstra (Father of Sikke)

Jan Hiemstra remained active as a blacksmith even after the war and continued to be beloved in the village. He was a familiar face in Oudega-W and was also a member of the sailing club in Workum. In addition, he owned his own ship, but eventually had to give up this hobby due to his health.

Jan Hiemstra on his sailboat somewhere near the Oudegaasterbrekken around 1946.

Jan Hiemstra in a news article.

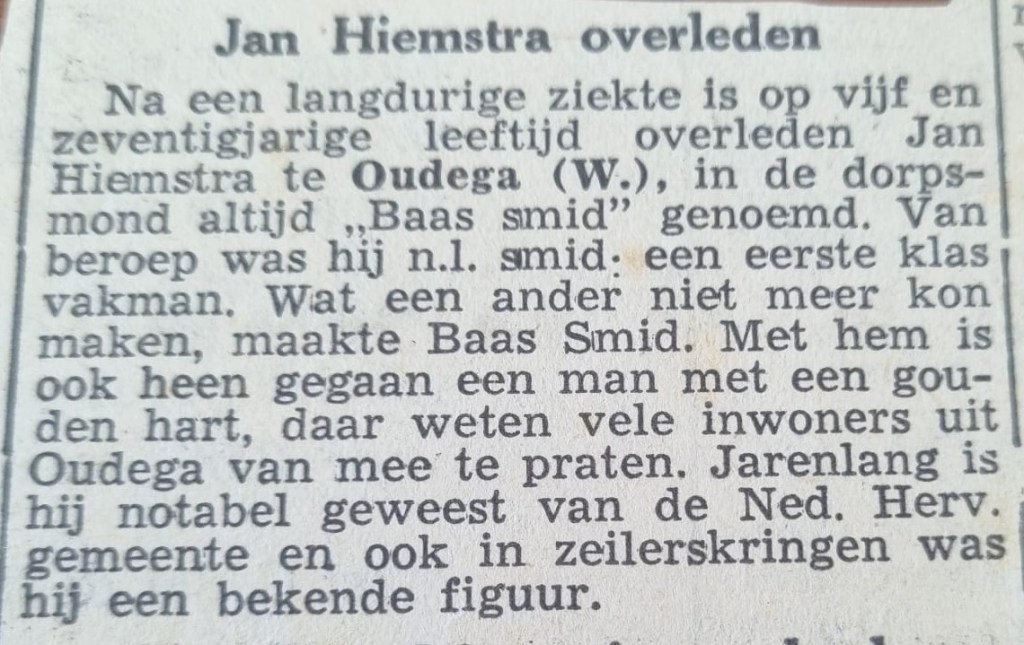

Eventually, Jan became ill. On August 25, 1951, he passed away at the age of 75. He was buried in an unmarked grave. According to family stories, he was buried by a competing blacksmith from Oudega-W, as this had been his final wish.

Jan Hiemstra working in his blacksmith.

A funeral notice for Jan Hiemstra, “Master Blacksmith.”

Fokke Hiemstra (Brother of Sikke) & Sietske van der Mark

Fokke remained in Germany until the end of World War II. The city where he had been assigned, Herford, came under the British occupation zone after the war. Presumably, he had to stay there for some time until the British had identified who he was. He probably was only allowed to return home sometime between 1945 and 1947. After the war, Fokke returned to Oudega and resumed his work at the post office. He was visited after the war by anti-Hitler Germans with whom he had stayed. Naturally, this caused some tension in the tiny village of Oudega-W, as a car with German license plates was very conspicuous after the war. According to Niene (Fokke’s sister), they were ‘spies.’

On September 2, 1947, Fokke married Sietske. According to family stories, Fokke was an excellent swimmer. During one incident, he fell into the water and had to dive under a ship as it approached. Afterwards, he was able to reach the shore safely. Fokke also maintained a good relationship with his brothers Andries and Sikke, and his sister Niene. Fokke ultimately passed away in 1989.

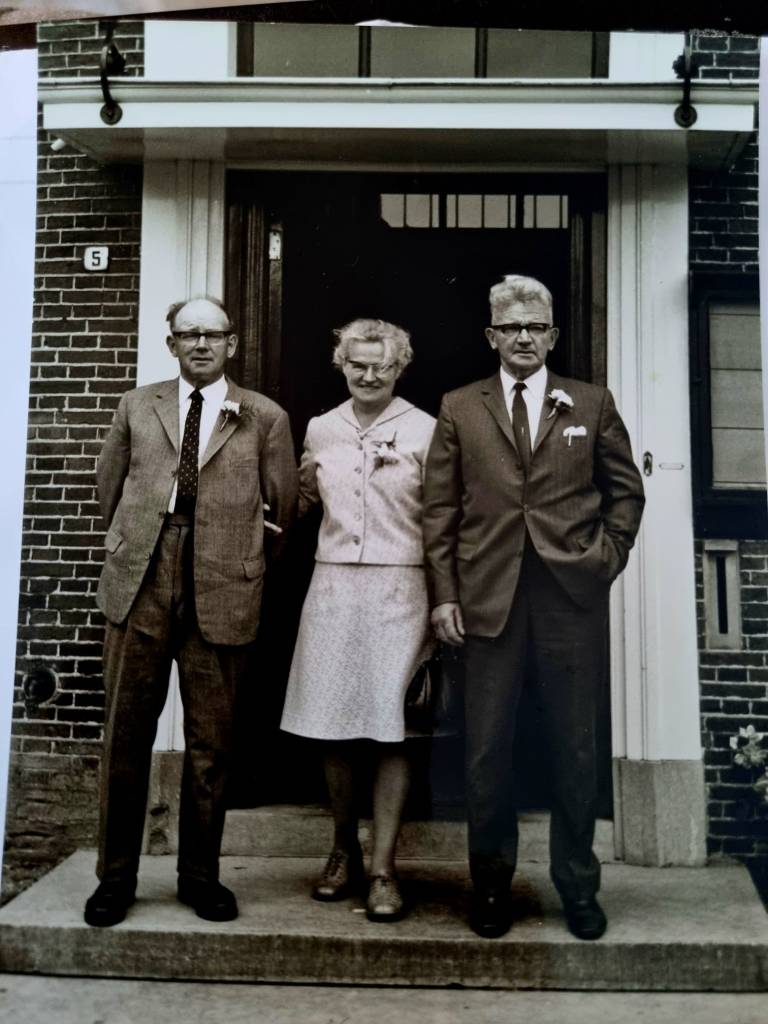

A photo with Fokke (left), Sietske (center), and Sikke (right). This photo was taken after the war.

Niene Hiemstra (Sister of Sikke) & Dirk ten Dam

Niene and Dirk remained happily married after the war and lived in Easterein. Dirk was still working in the butcher shop, where Niene often helped him. Nevertheless, Niene felt homesick for Oudega-W because this was the village where she had grown up and spent an important part of her life. Both Dirk and Niene maintained good contact with Sikke, Andries, Fokke, and the rest of the family.

They had three children: Wybren (the eldest), Jan (the middle), and Fokke (the youngest). Wybren eventually worked as a contractor on various projects in the Netherlands and abroad, including in Russia, China, and Egypt. Jan followed in his parents’ footsteps and also became a butcher. Fokke chose a different path and became an investigator with the FIOD.

Eventually, Niene passed away in 1990, and Dirk followed a year later, in 1991.

Niene with her three children: Wybren, Jan and Fokke.

Niene and Dirk later in life.

Andries Hiemstra (Brother of Sikke)

After the war, Andries continued working in his father’s blacksmith shop. In June 1947, he married Patricia van der Meer. Together, they had three children: Jan (John), Reta, and Kathy. After his father passed away, Andries and Patricia emigrated to Canada in 1953 with their children. They settled in the town of Orangeville.

A photo from the wedding of Andries Hiemstra and Patricia van der Meer. The photo also includes Sikke (left) and Jan Hiemstra (left), Niene and Ymkje (two women behind the bride in the back row), and Dirk (to the left of the man wearing a hat on the right).

Andries worked for several years at Imperial Oil and later became a contractor. In his later years, he also worked in the technical departments of hospitals in Toronto and Orangeville. Andries and Patricia remained active in the church. Since their arrival in Canada, they were involved with the Tweedsmuir Memorial Presbyterian Church. In later years, Andries and Patricia enjoyed gardening, and Andries sometimes tinkered with engines and bicycles. His son Jan (John) eventually became interested in engines as well and worked for many years at the Chrysler Motor Corps.

In the 1990s or early 2000s, Andries tried to apply for a resistance pension due to lasting injuries from his resistance activities. The consulate in Toronto conducted multiple interviews with him, but unfortunately, his request was denied. No one could verify his statements since most people from his resistance period had already passed away. This was especially difficult for him, particularly since other resistance members from Orangeville did receive a resistance pension.

Nevertheless, Andries never forgot his roots. He regularly wore wooden clogs, and his house was always decorated in orange whenever the Netherlands played in a European Championship or World Cup. He also frequently called his brothers and sister in the Netherlands, often speaking in Frisian. Andries ultimately reached the respectable age of 96 and passed away in 2013. His wife Patricia died a few years later, in 2019, at the age of 91. Andries and Patricia’s children are still living. Their son Jan (John) continues to engage with the history of World War II in the Netherlands. A few years ago, he visited several locations in the Netherlands together with his daughter and granddaughter.

Andries Hiemstra in orange during a World Cup. Naturally, he couldn’t leave his Dutch background behind.

Sikke Hiemstra & Ymkje de Jong

Sikke continued to work at the PWN even after the war and was responsible for the installation of various water pipelines throughout North Holland[1]. In addition, after the war, he became a member and eventually the secretary of the Christian Music Association Crescendo. Sikke had a musical background, having played in a military-style band in his youth. Ymkje and Sikke also had another son in the 1950s, Fokke Pieter (eventually called Cock).

Sikke was thanked on behalf of PWN for his dedication to the company on the occasion of his 25th work anniversary.

A homemade drawing by Sikke on the occasion of his service anniversary. Even after the war, he continued to draw.

In the 1950s, Sikke and Ymkje decided to move from Pieter Florisstraat to Veenenlaan. In the 1960s, they moved again, this time to Van de Blocqueriestraat. These streets were close to each other, so they did not move far. Sikke remained active as the Sacristan of the Eikstraat Church. In his free time, he enjoyed gardening, drawing, and writing. He also had his own small workshop when he lived at the Van de Blocqueriestraat. He was very inventive and made all sorts of things, such as copper candlesticks, ashtrays, letter openers, and footstools. This skill ran in the family because his father had been a blacksmith and knew how to make many things.

A candlestick, made of copper, crafted by Sikke.

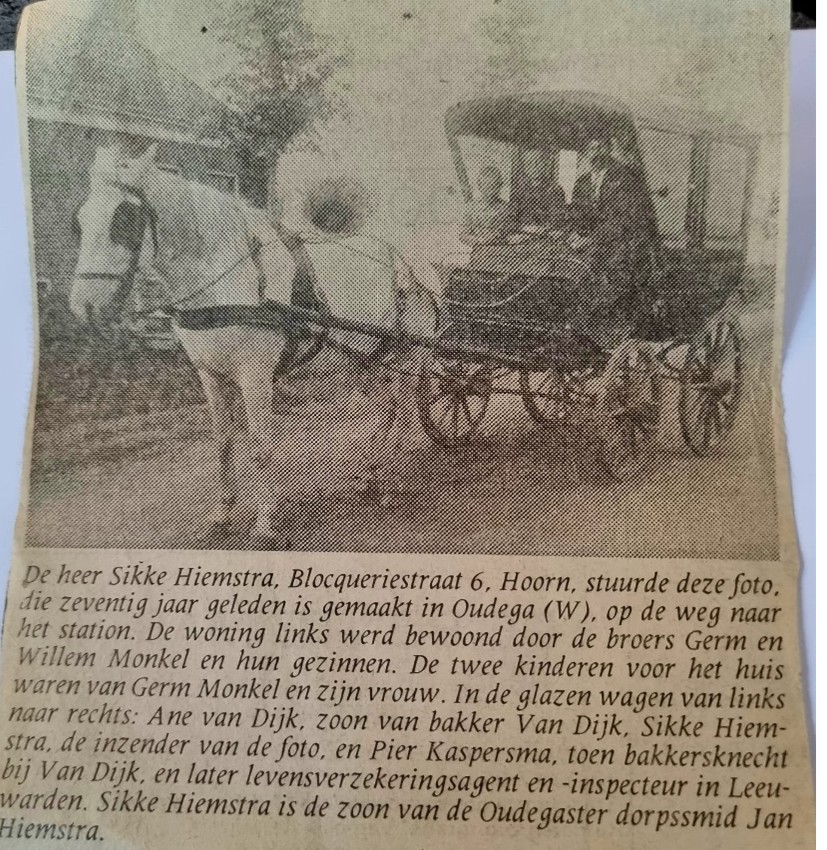

A submitted piece by Sikke Hiemstra.

Sikke and Ymkje regularly organized celebrations for their wedding anniversaries, always inviting the family. Sikke also maintained good contact with his brothers Fokke and Andries, and his sister Niene. In the 1980s, they were invited to a family reunion, with Andries traveling specifically from Canada to the Netherlands. At this reunion, a photo was taken of Niene, Sikke, Andries, and Fokke.

Sikke and Ymkje at their 25th marriage anniversary.

This photo was taken in the 1980s. From left to right: Sikke, Andries, Niene, and Fokke. As the photo shows, the bonds between them remained strong even after the war.

In 1989, Sikke’s wife passed away. From that moment, he lived in the Westerhaven nursing home in Hoorn. There, he read many books about Friesland and the Second World War in Friesland. He could sometimes have long conversations with himself about the past. Sikke reached the respectable age of 92 and passed away in 1997, two years before the birth of his great-grandson Lars Brull (1999).

Sikke and Ymkje at the marriage of their granddaughter.

Sikke continued to read about Friesland in the 1990s.

In total, Sikke and Ymkje had four children: Jan, Ank, Siep, and Cock. Jan became a display designer by profession and would later marry twice. Ank married Peter de Vries and became a housewife. They had three daughters and two grandchildren, including the author of this website. After her parents passed away, Ank came into possession of Sikke’s diary, which she carefully preserved for many years. Without her care, this piece of family history might have been lost. Both Ank and Jan have since passed away.

Siep became a house painter by profession and rode a Vespa. He also traveled abroad with his club, including destinations like England. In addition, he played tennis for many years. Siep is now 85 years old and happily married to his wife Annie. They have three children and several grandchildren. Siep is the only living person mentioned in Sikke’s diary since he was still a baby during 1939–1940. Both Siep and Jan followed in their father’s footsteps by serving in the military. Siep was a first-class soldier-writer for a few months, while Jan served in the military police. The youngest son, Cock, did not have to serve because the rules exempted the third brother from military service. Cock inherited his father’s musical talent and became a bassist in the band The Red Strats in the 1960s. He remained active in the band for many years. Today, their music is still available on YouTube. Later, Cock worked as an urban planning draftsman. He is now 78 years old, happily married to his wife Tineke, and they have two children and several grandchildren.

This photo was taken during the 50th wedding anniversary of Sikke and Ymkje. In the foreground sit Sikke and Ymkje, while their children are standing in the background. From left to right are Jan, Ank, Siep, and Cock. This photo was taken sometime in the 1980s.

Sikke rarely spoke about his mobilization period, so little was known within the family about that time until the diary came into the hands of his great-grandson Lars Brull. Lars decided to transcribe the diary, driven by his fascination with history. In 2023, Lars and his mother (Sikke’s granddaughter) applied to the Ministry of Defense for the Mobilization War Cross (MOK). This award was granted posthumously, recognizing Sikke’s service as a soldier during 1939–1940. Unfortunately, he was no longer alive to receive the decoration himself.

The Mobilization War Cross is still awarded today to veterans and the next of kin of military personnel who served during the period 1939–1940. On the back of the cross is inscribed: “Den Vaderlant Ghetrouwe.”

In 2024, exactly 85 years after the mobilization, Lars launched the website Soldaat Sikke Hiemstra, publishing the diary digitally. The website received media attention from outlets including Omroep Fryslân and the NOS. Many people read the story, gaining insight into the mobilization and Sikke’s experiences. More than 30 years after his passing, his story remains very much alive.

Sikke at a later age during his 50th wedding anniversary.

[1] PWN stands for Provincial Water Supply Company of North Holland. It is a drinking water company based in North Holland, where Sikke worked.

Sources

This section refers to external sources used for this webpage.

- 2 Registration of Foreigners and German Persecutees by Public Institutions, Social Securities and Companies (1939 – 1947) , 2.1.2.1/ 5532001/ ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives.

- 2 Registration of Foreigners and German Persecutees by Public Institutions, Social Securities and Companies (1939 – 1947) , 2.1.2.1/ DE ITS 2.1.2.1 NW 039 7 NIE ZM/ ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives.

- 75 jaar vrijheid, ‘Wat is de geschiedenis van Port Natal in Assen?’https://drenthe.75jaarvrijheid.nl/artikel/2430369/wat-is-de-geschiedenis-van-port-natal-in-assen (June 27, 2025).

- Archive Defence, Service card Sikke Hiemstra (batch 1925).

- Archive material, family de Vries.

- Archive material, family Hiemstra.

- Archive material, family ten Dam.

- Archive from the family ten Dam, Letter written by Andries Hiemstra to Jan Hiemstra (1943).

- Archive from the family ten Dam, Letter signed by the Lagerführer (1944).

- Bianca Stigter, ‘Atlas van het bezette Amsterdam (1940-1945)’, (version march 29, 2024) https://historiek.net/atlas-van-het-bezette-amsterdam-1940-1945/127560/ (May 13, 2025).

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, ‘Prijzen toen en nu,’ (Version march 21, 2013) https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/onze-diensten/leren-met-het-cbs/gereedschappen/prijzen-toen-en-nu (September 9, 2024).

- Comité 40-45 Hoorn, ‘Vliegtuigcrash boven Hoorn’ https://www.oorloginhoorn.nl/vliegtuigcrash-boven-hoorn/ (July 14, 2025).

- Comité 40-45 Hoorn, ‘Oorlog in Hoorn’ https://www.oorloginhoorn.nl/oorlog-in-hoorn/ (June 27, 2025).

- Delpher, ‘Venlo-Incident’, https://www.delpher.nl/thema/geschiedenis/venlo-incident#:~:text=De%20Telegraaf%2C%2013%20november%201939&text=Wat%20De%20Geer%20zich%20dan,inval%20in%20Nederland%20te%20rechtvaardigen (November 13, 2024).

- De Slag om de Grebbeberg en de Betuwestelling in mei 1940, ‘Geijkte misvatingen en mythes’, https://www.grebbeberg.nl/index.php?page=geijkte-misvattingen-en-mythes (February 9, 2025).

- De Slag om de Grebbeberg en de Betuwestelling in mei 1940, ‘Geweer en Karabijn M.95’, https://www.grebbeberg.nl/index.php?page=geweer-en-karabijn-m-95 (September 9, 2024).

- De Slag om de Grebbeberg en de Betuwestelling in mei 1940, ‘Lichte mitrailleur Lewis M.20’, https://www.grebbeberg.nl/index.php?page=lichte-mitrailleur-lewis-m-20 (September 27, 2024).

- De Slag om de Grebbeberg en de Betuwestelling in mei 1940, ‘Vuistvuurwapens’, https://www.grebbeberg.nl/index.php?page=vuistvuurwapens (December 16, 2024).

- De strijd om Westervoort, ‘Infanterie’, https://www.westervoort1940.nl/nl_troepen_infanterie.html (August 29, 2024).

- De strijd om Westervoort, ‘Infanterie Depotbataljons’, https://www.westervoort1940.nl/infanterie_depot_bataljons.html#opkomstdata (August 29, 2024).

- Dods & McNair Funeral Home, Chapel & Reception Centre, ‘In Memory of Patricia (Pietje) Riemke Hiemstra (Van der Meer)’ https://www.dodsandmcnair.com/memorials/patricia-pietje-hiemstra/3708663/obit.php?&printable=true (June 27, 2025).

- Douwe Bijlsma, ‘Overzicht van 4 mei-herdenkingen in De Fryske Marren’ (version may 4, 2025) https://www.grootfryslan.nl/nieuws/algemeen/110735/overzicht-van-4-mei-herdenkingen-in-de-fryske-marren (June 27, 2025).

- Drenthe in oorlog, ‘Dwangarbeiders bouwen Frieslandriegel of Assener Stellungen’https://www.drentheindeoorlog.nl/?aid=321#:~:text=In%20de%20nazomer%20van%201944,hout%20en%20halen%20vuilnis%20op (June 27, 2025).

- Eindhovensche en Meierijsche courant, ‘Landverraders in onze provincie? Lichtkogels bij Goirle afgeschoten, 23 Februari 1940, 9, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=KBDDD02:000199760:mpeg21:p009 (February 21, 2025).

- Eindhovensche en Meierijsche courant, ‘Weer lichtkogels nabij Zeist’, 23 Februari 1940, 5, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=KBDDD02:000199760:mpeg21:p005 (February 21, 2025).

- Eric van der most en Johan van Hoppe, ‘1940: verklaring op Erewoord’, https://krijgsgevangen.nl/verklaring-op-erewoord/ (August 19, 2024).

- Gaasterland in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, ‘Jeen Hornstra’ https://www.gaasterlandinwo2.nl/jeen-hornstra/ (June 27, 2025).

- Gaasterland in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, ‘Wapendroppings 2 Duitsers komen naar Gaasterland’ https://www.gaasterlandinwo2.nl/wapendroppings-2/ (June 27, 2025).

- Historiek, ‘De Hongerwinter van 1944-1945’ (version may 2, 2025), https://historiek.net/hongerwinter-1944-1945-hongersnood/69273/ (June 27, 2025).

- Historiek, ‘Geallieerd bombardement op Schiphol (1943)’, (Version January 8, 2025), https://historiek.net/geallieerd-bombardement-op-schiphol-1943/161022/ (May 10, 2025).

- Interviews, family de Vries.

- Interviews, family Hiemstra.

- Interviews, family ten Dam.

- James C. Kennedy, Een beknopte geschiedenis van Nederland (Amsterdam 2018) 323.

- Jephta Dullaart, ‘Fort Coehoorn’, (version may 15, 2024), https://onh.nl/verhaal/fort-coehoorn-gedroomd-fort-luidt-einde-van-de-stelling-van-amsterdam-in (April 23, 2025).

- Johannes Walinga, Tussen Brek en Skuttel, (1980) 122-125.

- Johannes Walinga, Tussen Brek en Skuttel II, (1986) 134-135.

- L. de Jong, Het koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog II, Neutraal (Den Haag 1969) 282-284, 447-448, 451-453, 460-461.

- Leeuwarder Courant, ‘Nederland en de Oorlog’, 7 mei 1940, 1, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010607960:mpeg21:p001 (May 7, 2025).

- Nationaal Archief, Archive of the red cross – Arbeidsinzet, archive inventory number2.19.323, inventory number 542 Kreis Herford.

- Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie, Den Haag, Gevechtsverslagen en -rapporten mei 1940, access 409, inventory number 480022.

- Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie, Den Haag, Gevechtsverslagen en -rapporten mei 1940, access 409, inventory number 489019.

- Nieuwe Haarlemsche courant, ‘Evenwichtige Neutraliteitspolitiek’, 13 April 1940, 2, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMNHA03:179205022:mpeg21:p00002 (April 13, 2025).

- NIOD, ‘Arbeidsinzet 1940-1945’ (version June 10, 2024), https://www.niod.nl/zoekgidsen/arbeidsinzet-1940-1945 (June 27, 2025).

- Online begraafplaats, ‘Grafinformatie’ https://www.online-begraafplaatsen.nl/zerken.asp?g=1188751 (June 27, 2025).

- Open Archieven, ‘Huwelijk (huwelijksakte) op 2 september 1947 te Idaarderadeel’ (version march 17, 2024), https://www.openarchieven.nl/frl:ea36f9b3-8c4f-4f4f-9ce7-6f840f128bd8 (June 27, 2025).

- Open Archieven, ‘Huwelijk op 5 juli 1944 te Wijmbritseradeel’ (version june 26, 2020) https://www.openarchieven.nl/frl:2ec08d17-942c-c9b4-5f49-b92329a899a0 (June 27, 2025).

- Open Archieven, ‘Huwelijk op 11 juni 1947 te Wonseradeel’ (version march 17, 2024), https://www.openarchieven.nl/frl:6f9aea05-d7c1-7885-af9f-0af2d067a499 (June 27, 2025).

- Provinciale Noordbrabantsche en ’s Hertogenbossche courant, ‘Geheimzinnige Signalen? Geval Spionage?’, 19 Februari 1940, 6, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMSADB01:000016900:mpeg21:p006 (February 21, 2025).

- Sikke Hiemstra, Diary Sikke Hiemstra: Mobilization 1939-1940, https://soldaatsikkehiemstra.com/dagboek/versie-ii/.

- Sociale Verzekeringsbank, Dhr. A.Hiemstra WBP/WUV cor. no. 323634 (received on june 27, 2025).

- Stadsarchief Amsterdam, ‘Zelfmoordpoging’, (version April 23, 2019) https://www.amsterdam.nl/stadsarchief/stukken/dood/zelfmoordpoging/#:~:text=Vierhonderd%20zelfmoorden,voor%20vervolging%20onder%20het%20naziregime (May 13, 2025).

- Susanne Hiemstra-Cage, ‘Lives Lived: Andy Hiemstra, 96’ (version may 14, 2013), https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/facts-and-arguments/lives-lived-andy-hiemstra-96/article11894896/ (June 27, 2025).

- The Red Strats, ‘In Vogelvlucht het muzikale ‘‘Sixties’’ verleden van Cock Hiemstra’ https://www.theredstrats.nl/cock.htm (June 27, 2025).

- Vereniging Oud Hoorn, ‘Hoorn, huizen, straten, mensen- database’ https://www.beeldbank-oudhoorn.nl/cgi-bin/hhsmboek.pl (June 27, 2025).

- Visit Friesland, ‘Ontploffing van een munitietrein’, https://www.friesland.nl/nl/locaties/242114622/ontploffing-van-een-munitietrein (July 14, 2025).

- Volskrant, ‘Mededeeling over legeronderdelen’, 18 mei 1940, 2, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ABCDDD:010845288:mpeg21:p002 (May 17, 2025).