The Netherlands mobilizes

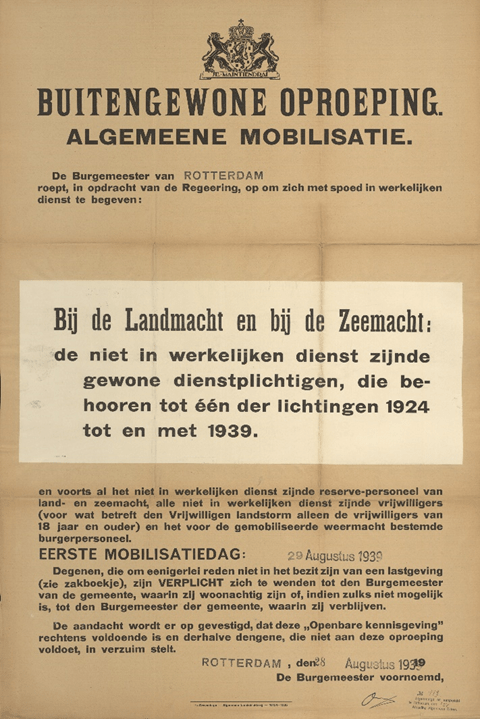

The pre-mobilization of the Dutch army began on August 24, 1939. This measure was intended to manage the mobilization wave that would follow later. On August 28, 1939, the Dutch government announced the full mobilization, bringing 280,000 conscripted men into service. 42,338 of these soldiers, were members of the Vrijwillige Landstorm, a group of armed citizens who supported the regular army.

The poster (from Rotterdam), which calls for the general Mobilization.

Many men had never fully completed their military service due to defense budget cuts in the 1920s and 1930s. In order to compensate for this, the army called up older soldiers around 35 years old. Therefore, many fathers left their families, leaving behind their children and wives.

Just a few days after the general mobilization, Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west on September 1, 1939. This marked the beginning of World War II. The Soviet Union attacked Poland from the east a few weeks later. Both Great Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany, as they wanted to guarantee Poland’s independence. At that moment, the Phony War began, during which Great Britain, France, and Nazi Germany did not engage in large-scale military actions on each other’s territories.

The Netherlands hoped to remain neutral during this unstable period, just as it had during World War I. After World War I, there were significant budget cuts to the Dutch military, leaving the country unprepared for war. The Dutch government did allocate more funds to the military between 1936 and 1940, however this did not solve the structural problems. As a result, the soldiers were insufficiently trained, the equipment was significantly outdated, there was a shortage of ammunition, and the air force was completely neglected.

To keep the soldiers occupied, committees for development and recreation (O&O) were established. These committees organized courses and other activities for conscripted soldiers. Additionally, various artists performed for the soldiers or made songs about the mobilization and the Dutch neutrality, such as Lou Bandy (1890-1959) with Rats, Kuch en Bonen, or Willy Walden (1905-2003) and Piet Muijselaar (1899-1978) with Blonde Mientje (based on the German marching song Erika). Furthermore, a magazine for soldiers called De Wacht—a weekly for the mobilized armed forces—was published. This led to the creation of a mobilization culture. Nevertheless, soldiers still had to perform their daily tasks, such as building fortifications, marching, cooking, standing guard, and sentry duty. After all, the soldiers did not know when the enemy might invade. Many of these daily tasks were carried out during the winter of 1939-1940, the coldest since 1845. This winter can be characterized as the mobilization winter.

The daily life of Dutch citizens were also affected by the mobilization. The army quartered soldiers in homes, schools, buildings, and farms. As a result, soldiers were increasingly seen in villages and cities. Furthermore, the Dutch army also requisitioned horses and vehicles from civilians. Additionally, some areas were flooded (inundatie) to hold off the enemy in case of an attack. Therefore, some families had to leave their farms, as they were flooded.

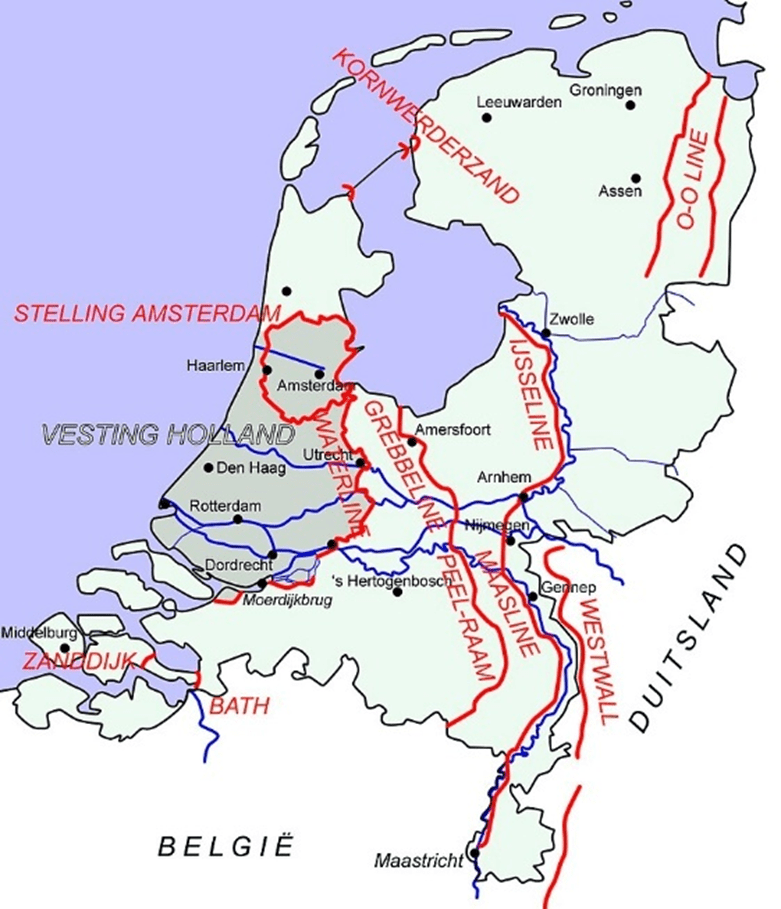

The Dutch mobilization not only brought changes for civilians, but also led to shifts within the military leadership. Dutch General Izaäk Reijnders (1879-1966) was continually in conflict with the Minister of War Adriaan Dijxhoorn (1889-1953) during the mobilization period. As a result, the Dutch government decided to look for a replacement. General Henri Winkelman (1876-1952) took over on February 6, 1940. He concentrated the Dutch defense at the Grebbe Line, unlike General Reijnders . This is where heavy fighting would occur in May 1940.

Flooding near the Grebbe Line.

During the mobilization, the first Dutch war casualties also occurred. In September 1939, the minesweeper Hr. Ms. Willem van Ewijck sailed over a Dutch mine, causing the ship to break in two and sink. This incident cost the lives of approximately 33 crew members. In November 1939, the Dutch passenger ship the Simon Bolivar struck two German naval mines off the British coast, resulting in the deaths of approximately eighty people. This marked the first Dutch civilian deaths during World War II.

There was also a lot of espionage during the mobilization. Reconnaissance planes from France, Belgium, and Nazi Germany violated Dutch airspace. German officers traveled to the Netherlands in civilian clothes for “vacations”, during which they mapped out Dutch defenses. Several incidents also occurred, such as the Venlo incident in November 1939. During the Venlo incident, two British agents from the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) were kidnapped by the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD) on Dutch territory. The Netherlands was still neutral at the time, so this incident caused a stir. Another significant incident took place on January 10, 1940, when a German plane made an emergency landing near the Belgian town of Vucht. Onboard were plans for an attack on Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The Belgian authorities passed this information on to the Netherlands. Although the Netherlands was initially skeptical, it was decided not to grant any more leaves.

Furthermore, the Netherlands also had a military attaché in Berlin, Major Bert Sas (1892-1948). He had close contact with his friend and officer Hans Oster (1887-1945), who regularly informed him about the German invasion plans for the Netherlands. Sas passed this information on to the Dutch authorities, but over time, the Dutch military leadership no longer believed Sas because the attack was continually postponed. One day before the German invasion, Sas said the famous words: “Tomorrow morning at the break of dawn. Stay tough.”

The Dutch defense lines.